Description

© 1988 Electronic Arts & Interplay Productions

Barry Edward Jackson is a renowned illustrator and concept artist known for his extensive work in the entertainment industry, including film, animation, and video games. He has a distinctive style that often incorporates vivid colours and dynamic compositions, which have made him a sought-after artist in various creative fields.

Barry Jackson began his career with a strong foundation in traditional art skills, studying at institutions that emphasized classical art techniques. He quickly transitioned into the entertainment industry, where he began to apply his skills to more modern mediums.

Jackson has worked on a number of high-profile film projects, contributing his skills as a concept artist and production designer. His film credits include work on Tim Burton’s “The Nightmare Before Christmas” and “James and the Giant Peach,” where his unique ability to blend the whimsical with the macabre shone through.

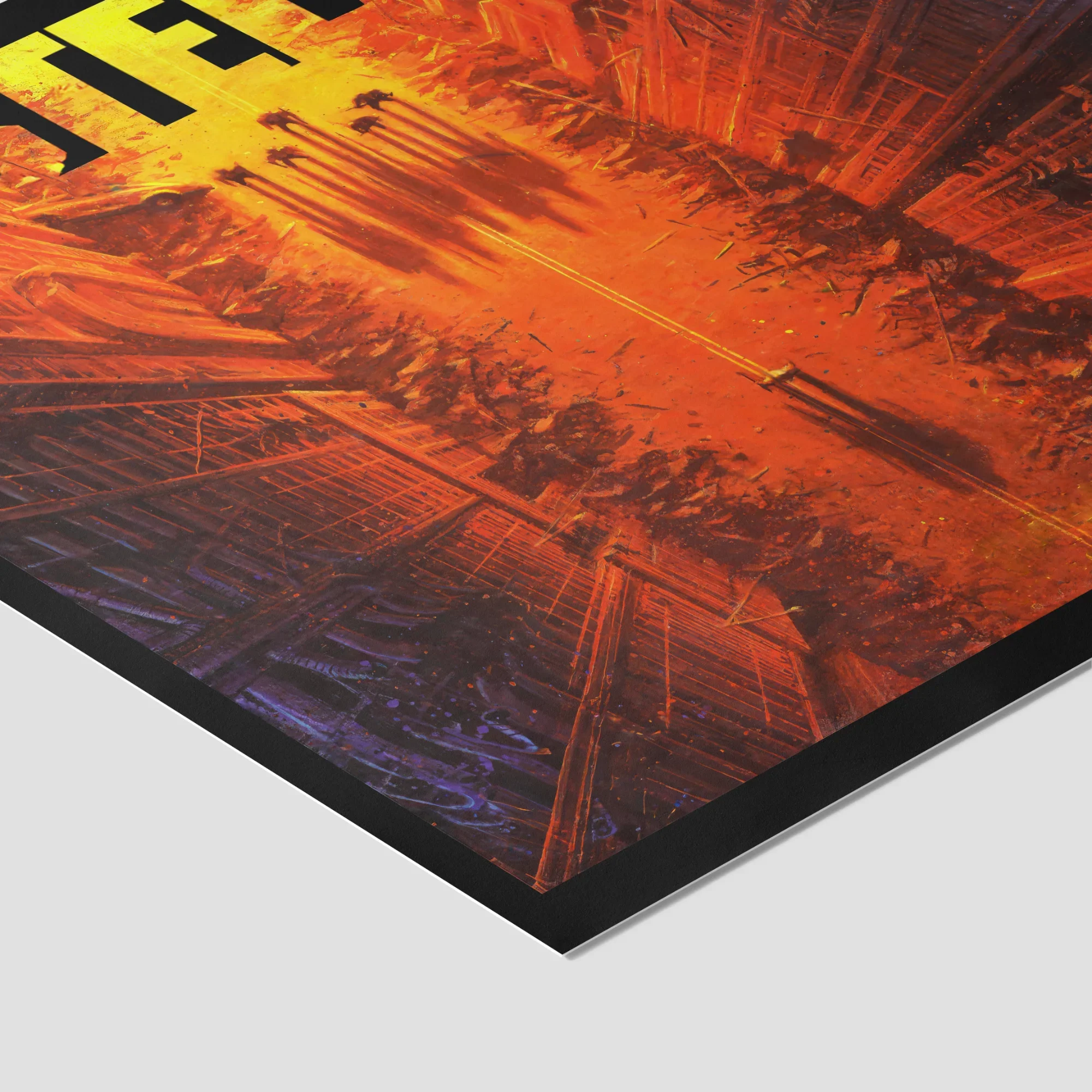

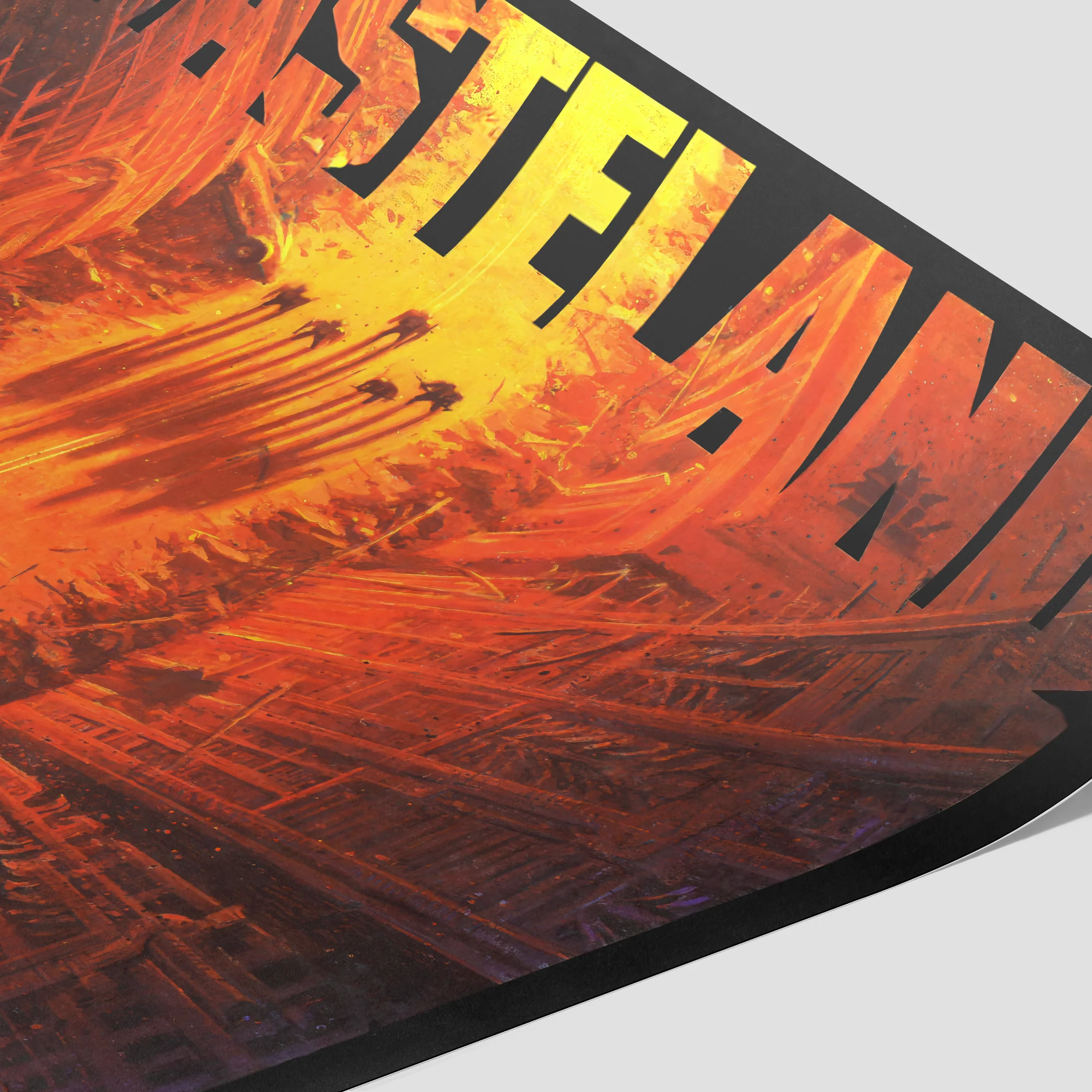

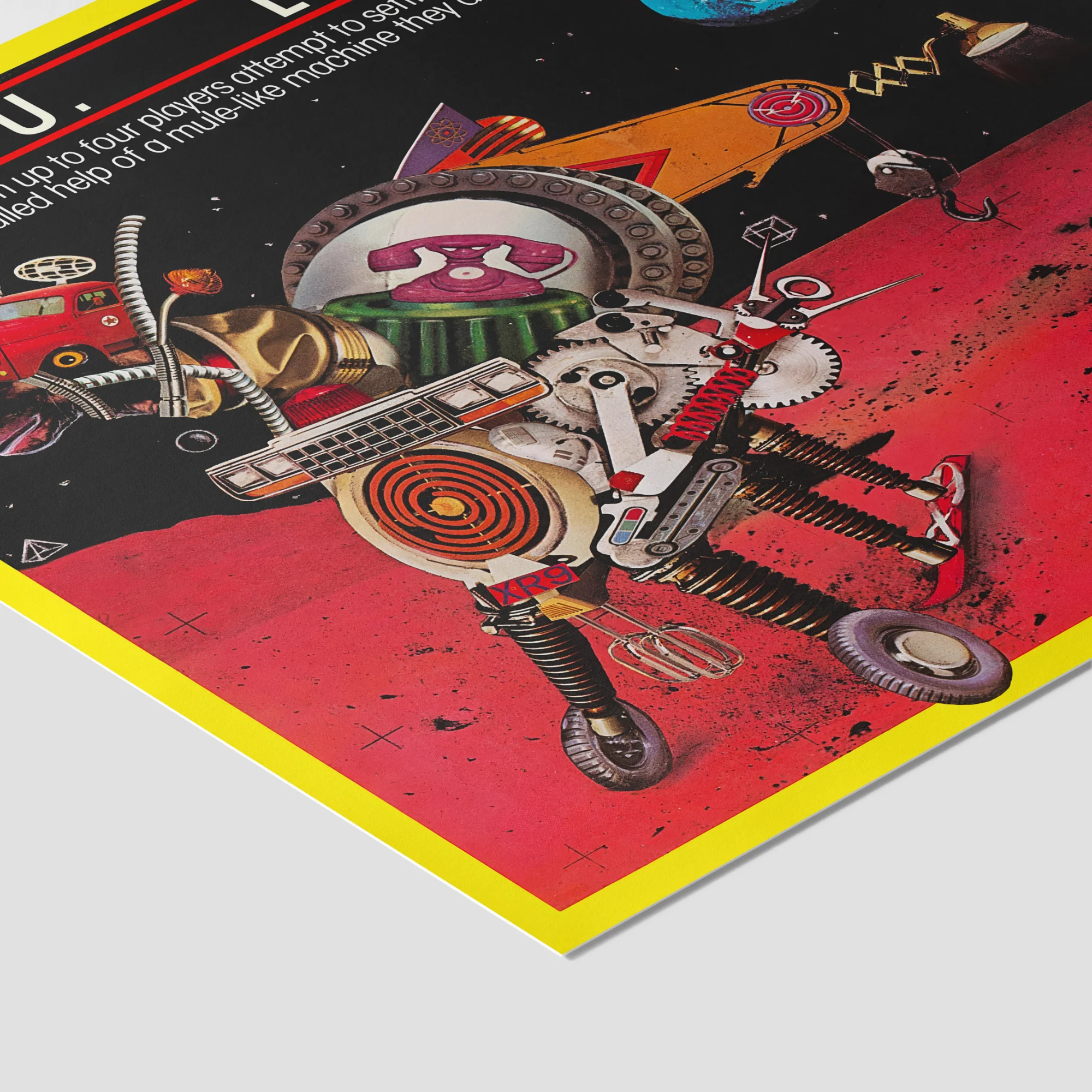

In the realm of video games, Barry Jackson has lent his artistic talents to several notable titles like Wasteland & Medal of Honour. After a two-year stint as writer and director of storyboard at Electronic Arts he left 2006 for Warner Bros. to produce the all-digital feature film “The Ant Bully”.

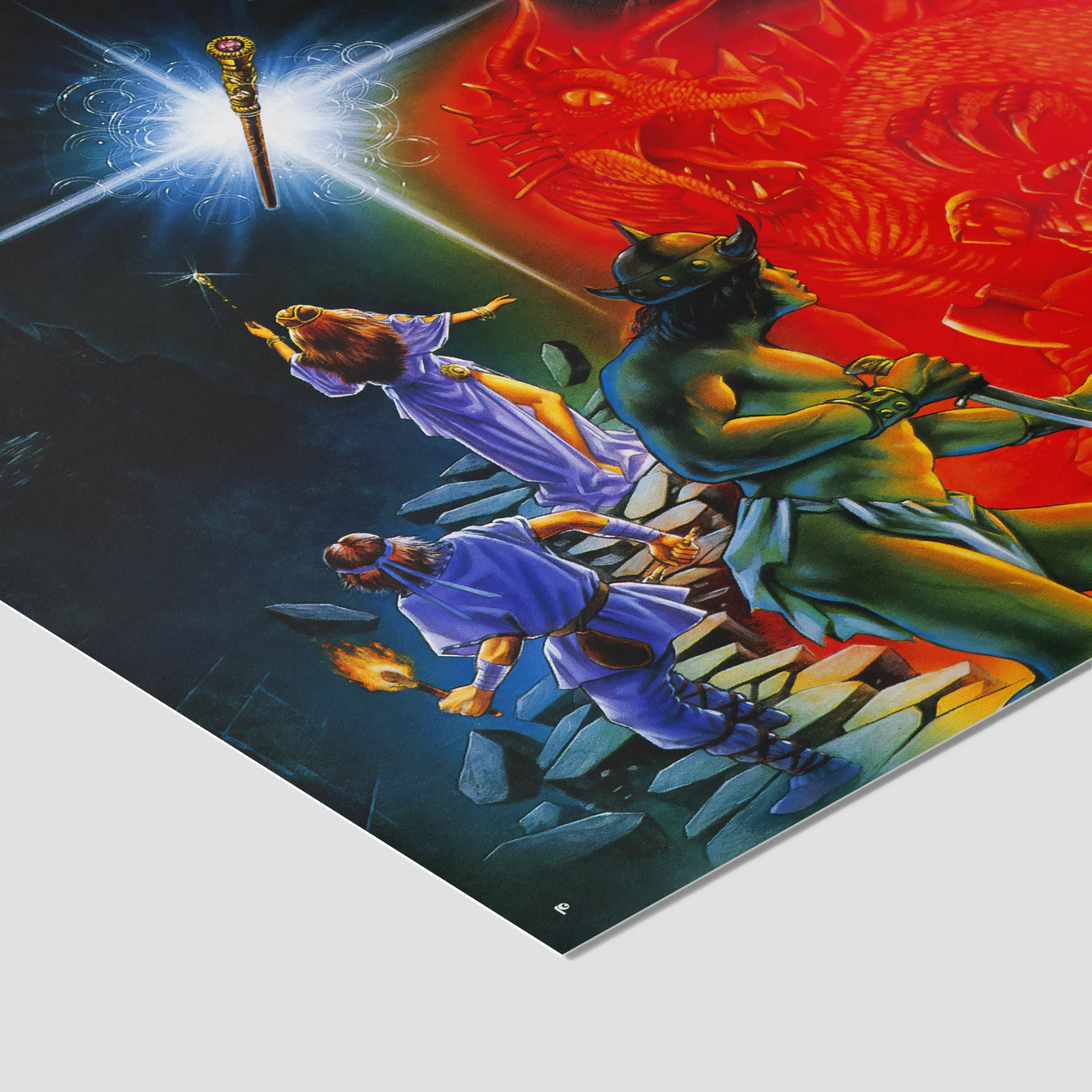

Interplay Productions, known simply as Interplay Entertainment, is a significant player in the video game industry with a history that spans several decades. Founded in 1983 by Brian Fargo, Interplay established itself as a developer and publisher of video games, contributing numerous memorable titles to the gaming landscape.

Interplay is renowned for its role-playing games (RPGs), with some of its most iconic titles including “The Bard’s Tale” series and “Wasteland,” the latter of which is considered a progenitor of the post-apocalyptic RPG genre and influenced the development of the “Fallout” series. Throughout the late 1980s and 1990s, Interplay enjoyed considerable success thanks to these titles, as well as through other genres. They expanded into action and adventure games, most notably with the “Descent” series, which was praised for its innovative fully 3D gameplay in a spaceship setting.

During the 1990s, Interplay expanded its portfolio by establishing divisions like Black Isle Studios, which became famous for its work on the “Fallout” series and for publishing several well-received Dungeons & Dragons games, including “Planescape: Torment” and the “Icewind Dale” series. They also ventured into publishing games developed by other studios, which helped diversify their offerings and expand their impact on the industry.

Despite early success, Interplay faced financial difficulties in the late 1990s and early 2000s, leading to the sale of significant assets and changes in ownership. One of the most impactful sales was the “Fallout” franchise to Bethesda Softworks, which went on to rejuvenate the series with new titles.

After facing bankruptcy and other financial challenges, Interplay has scaled back its operations considerably. The company now focuses mainly on licensing its existing properties and IP, maintaining a much lower profile in the industry compared to its heyday in the 1990s.

Interplay’s legacy in the video game industry is marked by its pioneering role in developing complex RPGs and engaging narratives that have influenced countless other games.

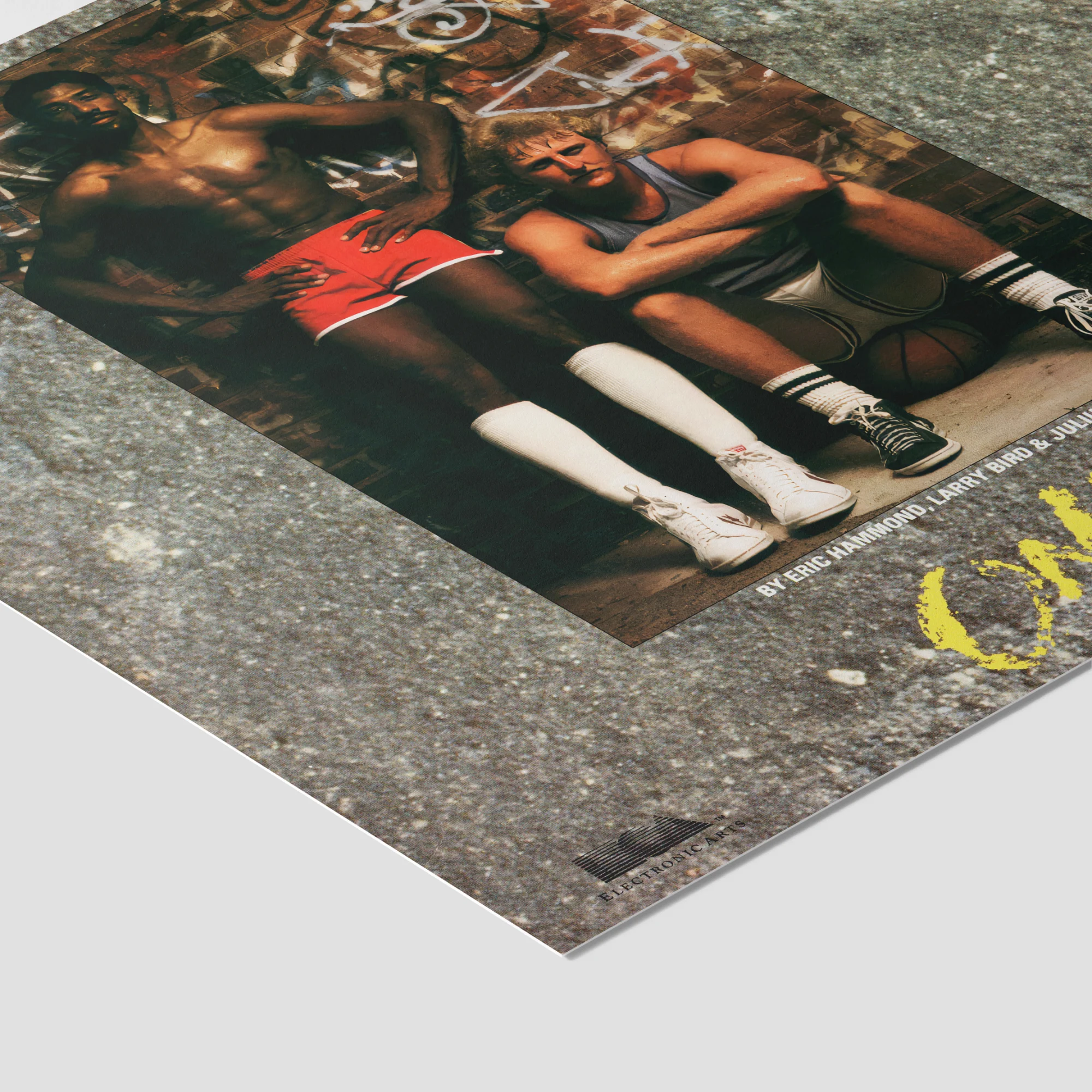

The “We See Farther” campaign launched by Electronic Arts (EA) in 1983 was a pioneering advertising effort aimed at redefining the perception of video games and their creators. Captured by renowned rock’n’roll photographer Norman Seeff, the campaign featured EA’s software developers styled as “software artists,” suggesting a kinship with rock stars in terms of creativity and importance. This early portrayal highlighted the potential of video games as a serious art form and emotional medium, challenging existing notions of games as mere novelties. The campaign included thought-provoking slogans like “Can a computer make you cry?” to emphasize the emotional depth that video games could evoke, setting a visionary precedent for the industry.

Simultaneously, EA began to revolutionize game packaging by adopting an art style reminiscent of rock album covers, complete with gatefold sleeves. This not only differentiated their products on shelves but also elevated the perceived value and cultural relevance of video games. Each package was designed to tell a story, engaging players with vivid illustrations and elaborate backstories that enriched the gaming experience.

EA used this kind of packaging until 1988 when the gatefold style faded out and was replaced by regular boxes.